Mid-Autumn Festival

| Mid-Autumn Festival | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||

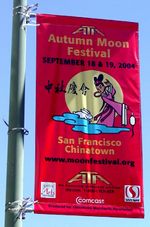

| The Mid-Autumn Moon Festival is also celebrated in Chinese communities such as the San Francisco Chinatown. | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中秋節 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中秋节 | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Min name | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 八月節 | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||

| Quốc ngữ | Tết Trung Thu | ||||||||||||||

| Chữ nôm | 節中秋 | ||||||||||||||

The Mid-Autumn Festival, also known as the Moon Festival, Zhongqiu Festival, or in Chinese, Zhongqiujie (traditional Chinese: 中秋節), or in Vietnamese "Tết Trung Thu", is a popular harvest festival celebrated by Chinese and Vietnamese people, dating back over 3,000 years to moon worship in China's Shang Dynasty. It was first called Zhongqiu Jie (literally "Mid-Autumn Festival") in the Zhou Dynasty.[1] In Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines, it is also sometimes referred to as the Lantern Festival or Mooncake Festival.

The Mid-Autumn Festival is held on the 15th day of the eighth month in the Chinese calendar, which is usually around late September or early October in the Gregorian calendar. It is a date that parallels the autumnal equinox of the solar calendar, when the moon is supposedly at its fullest and roundest. The traditional food of this festival is the mooncake, of which there are many different varieties.

The Mid-Autumn Festival is one of the few most important holidays in the Chinese calendar, the others being Chinese New Year and Winter Solstice, and is a legal holiday in several countries. Farmers celebrate the end of the summer harvesting season on this date. Traditionally on this day, Chinese family members and friends will gather to admire the bright mid-autumn harvest moon, and eat moon cakes and pomelos under the moon together. Accompanying the celebration, there are additional cultural or regional customs, such as:

- Putting pomelo rinds on one's head

- Carrying brightly lit lanterns, lighting lanterns on towers, floating sky lanterns

- Burning incense in reverence to deities including Chang'e (Chinese: 嫦娥; pinyin: Cháng'é)

- Planting Mid-Autumn trees

- Collecting dandelion leaves and distributing them evenly among family members

- Fire Dragon Dances

- In Taiwan, since the 1980s, barbecuing meat outdoors has become a widespread way to celebrate the Mid-Autumn Festival.[2][3]

Shops selling mooncakes before the festival often display pictures of Chang'e floating to the moon.

Contents |

Stories of the Mid-Autumn Festival

Houyi and Chang'e

Celebration of the Mid-Autumn Festival is strongly associated with the legend of Houyi and Chang'e, the Moon Goddess of Immortality. Tradition places these two figures from Chinese mythology around 2170 BCE, during the reign of the legendary Emperor Yao, shortly after that of Huangdi. Unlike many lunar deities in other cultures who personify the moon, Chang'e simply lives on the moon but is not the moon per se.

There are many variants and adaptations of the legend of Chang'e that frequently contradict each other. However, most versions of the legend involve some variation of the following elements: Houyi, the Archer, an emperor, either benevolent or malevolent, and an elixir of life.

One version of the legend states that Houyi was an immortal and Chang'e was a beautiful young girl, working in the palace of the Jade Emperor (the Emperor of Heaven, 玉帝 pinyin:Yùdì) as an attendant to the Queen Mother of the West (the Jade Emperor's wife). Houyi aroused the jealousy of the other immortals, who then slandered him before the Jade Emperor. Houyi and his wife, Chang'e, were subsequently banished from heaven. They were forced to live on Earth. Houyi had to hunt to survive and became a skilled and famous archer.

At that time, there were ten suns, in the form of three-legged birds, residing in a mulberry tree in the eastern sea. Each day one of the sun birds would have to travel around the world on a carriage, driven by Xihe, the 'mother' of the suns. One day, all ten of the suns circled together, causing the Earth to burn. Emperor Yao, the Emperor of China, commanded Houyi to use his archery skill to shoot down all but one of the suns. Upon completion of his task, the Emperor rewarded Houyi with a pill that granted eternal life. Emperor Yao advised Houyi not to swallow the pill immediately but instead to prepare himself by praying and fasting for a year before taking it.[4] Houyi took the pill home and hid it under a rafter. One day, Houyi was summoned away again by Emperor Yao. During her husband's absence, Chang'e, noticed a white beam of light beckoning from the rafters, and discovered the pill. Chang'e swallowed it and immediately found that she could fly. Houyi returned home, realizing what had happened he began to reprimand his wife. Chang'e escaped by flying out the window into the sky.[4]

Houyi pursued her halfway across the heavens but was forced to return to Earth because of strong winds. Chang'e reached the moon, where she coughed up part of the pill.[4] Chang'e commanded the hare that lived on the moon to make another pill. Chang'e would then be able to return to Earth and her husband.

The legend states that the hare is still pounding herbs, trying to make the pill. Houyi built himself a palace in the sun, representing "Yang" (the male principle), in contrast to Chang'e's home on the moon which represents "Yin" (the female principle). Once a year, on the fifteenth day of the full moon, Houyi visits his wife. That is the reason why the moon is very full and beautiful on that night.[4]

This description appears in written form in two Western Han dynasty (206 BC-24 AD) collections; Shan Hai Jing, the Classic of the Mountains and Seas and Huainanzi, a philosophical classic.[5]

Another version of the legend, similar to the one above, differs in saying that Chang'e swallowed the pill of immortality because Peng, one of Houyi's many apprentice archers, tried to force her to give the pill to him. Knowing that she could not fight off Peng, Chang'e had no choice but to swallow the pill herself.

Other versions say that Houyi and Chang'e were still immortals living in heaven at the time that Houyi killed nine of the suns. The sun birds were the sons of the Jade Emperor, who punished Houyi and Chang'e by forcing them to live on Earth as mortals. Seeing that Chang'e felt extremely miserable over her loss of immortality, Houyi decided to find the pill that would restore it. At the end of his quest, he met the Queen Mother of the West, who agreed to give him the pill, but warned him that each person would only need half a pill to regain immortality. Houyi brought the pill home and stored it in a case. He warned Chang'e not to open the case, and then left home for a while. Like Pandora in Greek mythology, Chang'e became curious. She opened up the case and found the pill, just as Houyi was returning home. Nervous that Houyi would catch her, discovering the contents of the case, she accidentally swallowed the entire pill, and started to float into the sky because of the overdose.

Some versions of the legend do not refer to Houyi or Chang'e as having previously been immortals and initially present them as mortals instead.

There are also versions of the story in which Houyi is rewarded for killing nine of the suns and saving the people by being made king. However, King Houyi became a despot. He gained the pill of immortality, either by stealing it from the Queen Mother of the West or by learning that he could make pills by grinding up the body of an adolescent boy every night for a hundred nights. Chang'e stole the pill and swallowed it herself, either to stop more boys being killed or to prevent her husband's tyrannical rule from lasting forever.

The Hare or The Jade Rabbit

According to tradition, the Jade Rabbit pounds medicine, together with the lady, Chang'er, for the gods. Others say that the Jade Rabbit is a shape, assumed by Chang'e herself. The dark areas to the top of the full moon may be construed as the figure of a rabbit. The animal's ears point to the upper right, while at the left are two large circular areas, representing its head and body.[6]

In this legend, three fairy sages transformed themselves into pitiful old men, and begged for food from a fox, a monkey, and a hare. The fox and the monkey both had food to give to the old men, but the hare, empty-handed, jumped into a blazing fire to offer his own flesh instead. The sages were so touched by the hare's sacrifice and act of kindness that they let him live in the Moon Palace, where he became the "Jade Rabbit".

Overthrow of Mongol rule

According to a widespread folk tale (not necessarily supported by historical records), the Mid-Autumn Festival commemorates an uprising in China against the Mongol rulers of the Yuan Dynasty (1280–1368) in the 14th century.[7] As group gatherings were banned, it was impossible to make plans for a rebellion.[7] Noting that the Mongols did not eat mooncakes, Liu Bowen (劉伯溫) of Zhejiang Province, advisor to the Chinese rebel leader Zhu Yuanzhang, came up with the idea of timing the rebellion to coincide with the Mid-Autumn Festival. He sought permission to distribute thousands of moon cakes to the Chinese residents in the city to bless the longevity of the Mongol emperor. Inside each cake, however, was inserted a piece of paper with the message: "Kill the Mongols on the 15th day of the 8th month" (traditional Chinese: 八月十五殺韃子; simplified Chinese: 八月十五杀鞑子).[7] On the night of the Moon Festival, the rebels successfully attacked and overthrew the government. What followed was the establishment of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), under Zhu. Henceforth, the Mid-Autumn Festival was celebrated with moon cakes on a national level.

Vietnamese version

The Mid-Autumn festival is named "Tết Trung Thu" in Vietnamese.

The Vietnamese version of the holiday recounts the legend of Cuội, whose wife accidentally urinated on a sacred banyan tree, taking him with it to the Moon. Every year, on the mid-autumn festival, children light lanterns and participate in a procession to show Cuội the way to Earth.[8]

In Vietnam, Mooncakes are typically square rather than round, though round ones do exist. Besides the indigenous tale of the banyan tree, other legends are widely told including the story of the Moon Lady, and the story of the carp who wanted to become a dragon.[8]

One important event before and during Vietnamese Mid-Autumn Festival are lion dances. The dances are performed by both non-professional children group and trained professional groups. Lion dance groups perform on the streets go to houses asking for permission to perform for them. If accepted by the host, "the lion" will come in and start dancing as a wish of luck and fortune and the host gives back lucky money to show thankfulness.

Dates

The moon festival will occur on these days in coming years:[9]

- 2010: September 22

- 2011: September 12

- 2012: September 30

- 2013: September 19

- 2014: September 8

- 2015: September 27

- 2016: September 15

- 2017: October 4

- 2018: September 24

- 2019: September 13

- 2020: October 1

See also

- Chinese New Year

- Chinese holidays

- List of Harvest Festivals

- Tsukimi, analogous Japanese festival

- Tidal bore of Qiantang River

- Vietnamese holidays

- Vietnamese culture

References

- ↑ Chinese language article about references to the Mid Autumn festival in ancient Chinese text - chinapage.com

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Chinatown.com.au

- ↑ Shanghai me

- ↑ Chinatown Online - your guide to all things Chinese

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Examination of the legend against the historical backdrop of mongol dynasty

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 familyculture.com tettrungthu

- ↑ "Chinese Lunar Network" (in Simplified Chinese). http://nongli114.com/index.php/lunarHoliday/2009/21.html.

External links

- Lantern Festival Mid-Autumn Lantern Carnival Planning & Production

- Autumn Moon Festival in San Francisco Chinatown

- Autumn Moon Festival in Australia

- chinatown.com.au

- The Stories of the Chinese Moon Festival

- Origin of Mid-Autumn Festival

- Têt Trung Thu

- More photos of Mid-Autumn Festival

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||